An Assessment of Outreach and Enrollment Activities Funded by the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act

Children's access to health insurance in the United States has improved greatly over the last 20 years. Among children in low-income families the rate of uninsurance has dropped from around 25% to 6% (Current Population Survey 1998; Zammitti et al. 2017). The availability of public health insurance through Medicaid and the Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which was created in 1997, has driven the improvement. Other factors include outreach, enrollment, and renewal innovations and adult eligibility expansions in many states (Lewit 2014). Federal, state, and local efforts to increase the enrollment of eligible children have been highly effective. In 2015, the national Medicaid and CHIP participation rate among eligible children without private coverage was 93 percent (Kenney et al. 2017).

Despite this progress, about 3.6 million children remain uninsured (Zammitti et al. 2017). Most (3.2 million) are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP (Rudowitz et al. 2016). Among eligible children, uninsurance is more common for teens, Hispanic/Latino children, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) children, those in households with very low income, and those living outside metropolitan areas (Kenney et al. 2016).

To enroll and retain more eligible children in Medicaid and CHIP, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Connecting Kids to Coverage (CKC) National Campaign in 2009. The CKC National Campaign has three primary goals:

- Raise awareness about Medicaid and CHIP coverage

- Motivate parents to enroll their eligible children and teenagers and renew their coverage

- Provide free materials and guides to help states, community groups, and others conduct successful outreach activities

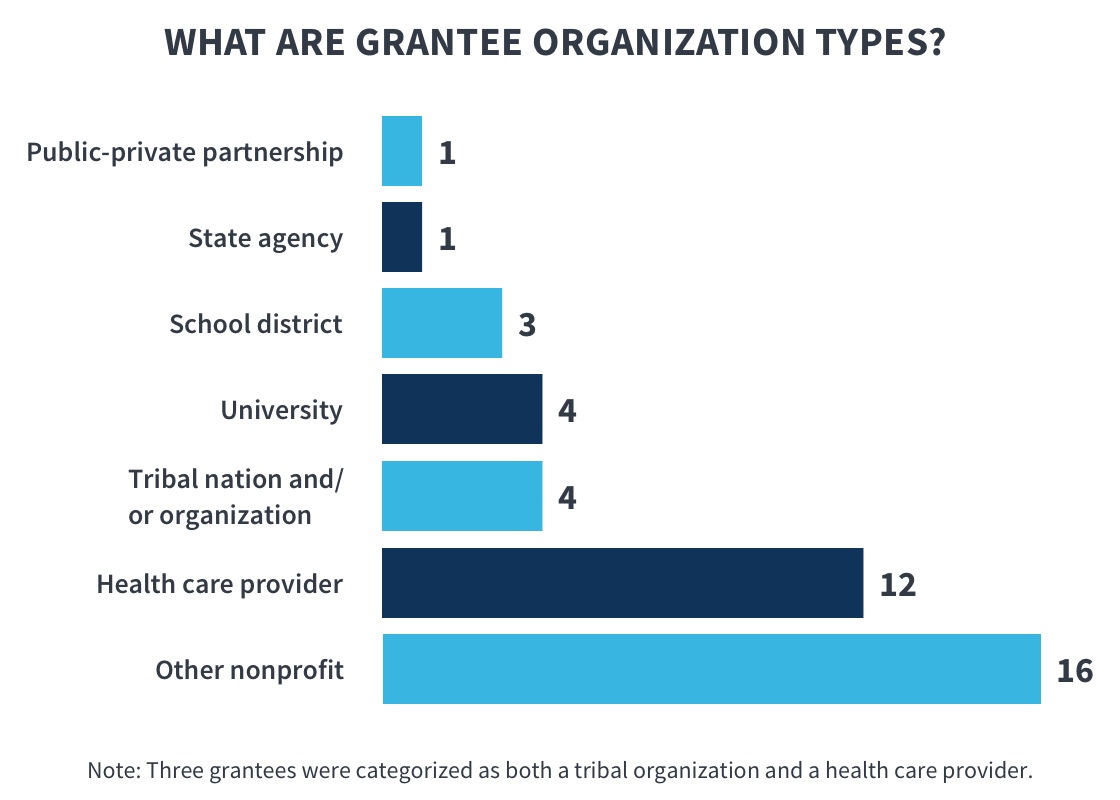

In conjunction with the Campaign, CMS has awarded CKC outreach and enrollment grants to a variety of community organizations—such as health care providers, school systems, tribal organizations, states and local government agencies, and various nonprofits—through four two-year funding cycles since 2009 (InsureKidsNow.gov 2017a). CMS also has a separate grant program with the express purpose of increasing Medicaid and CHIP enrollment among eligible AI/AN children (InsureKidsNow.gov 2017b). These AI/AN grants were awarded in 2010, 2014, and 2017 (Ibid.). To date, CMS has made available $162 million to eligible entities to support the enrollment and retention of eligible children in Medicaid and CHIP. Community and tribal organizations usually have access to and credibility with low-income families in their communities. This standing makes such organizations indispensable partners for carrying out specialized strategies to target the eligible hard-to-reach children who remain uninsured. States and local governments are also eligible entities because of their ability, through partnerships with other human services programs, to identify uninsured children and enroll them in coverage. State and local government agencies also have relationships with local community organizations that can be leveraged to support outreach and enrollment efforts. Thus far, over 230 eligible entities have received CKC grants.

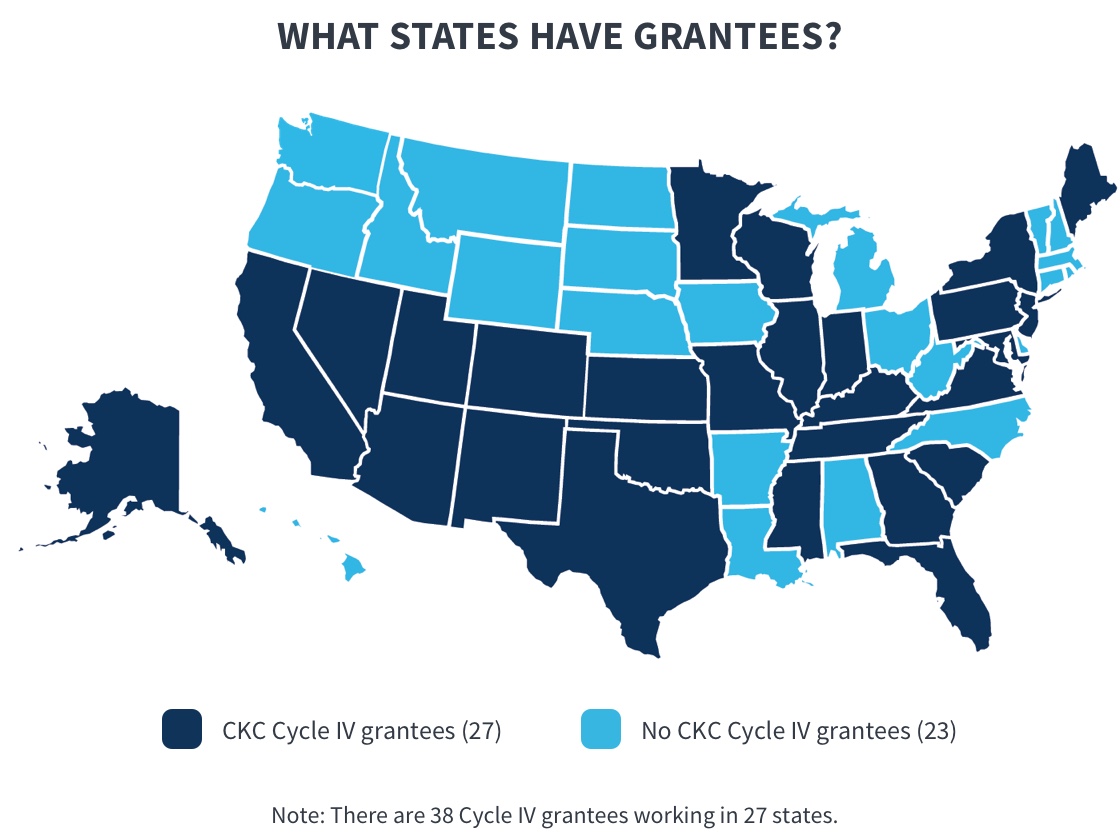

In July 2016, CMS provided grants to 38 organizations in 27 states through the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act CKC funding opportunity. Although the primary purpose of the CKC grants is to help eligible children enroll or renew their coverage, some Cycle IV grantees try to reach more children by also enrolling eligible parents into Medicaid or Marketplace insurance for which they qualify. CMS encouraged this new approach because research indicates that when parents gain coverage, they are more likely to cover their children (Georgetown University Health Policy Institute 2017).

CMS contracted with Mathematica Policy Research to evaluate and report on grantees' performance, and to provide technical assistance to help support grantees. This first annual evaluation summary is based on a review of grantees' progress reports covering the first year of their two-year grants, July 2016 through June 2017.

Key Findings

Outcomes

Many families benefited from grantees' efforts during the first year of Cycle IV:

- CKC grantees collectively supported the submission of nearly 80,000 child applications or renewal forms. Almost 55,000 children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP or renewed coverage as a result. Grantees also helped about 16,000 parents enroll or renew coverage.

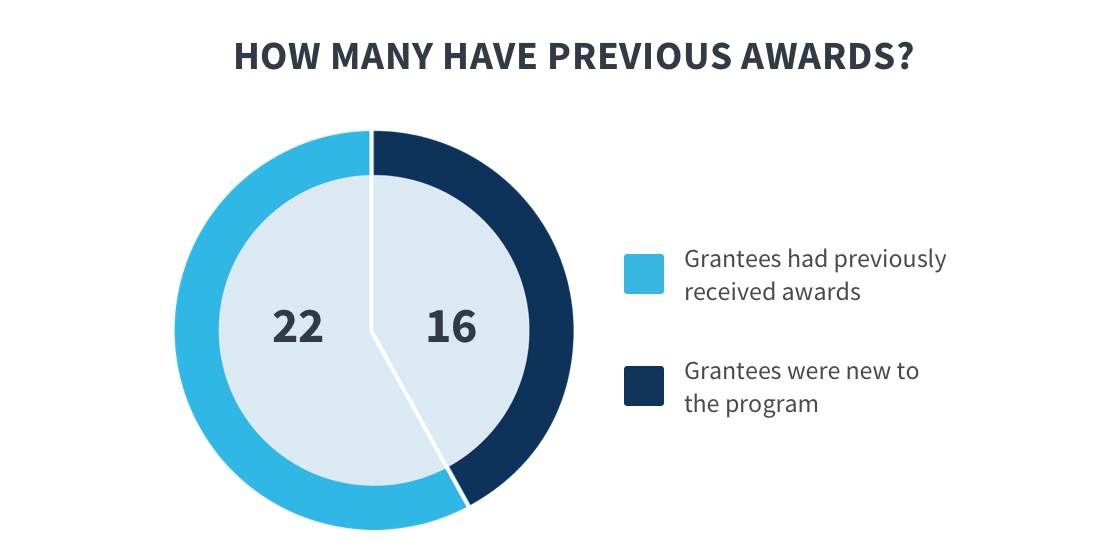

Some grantees contributed more to this achievement than others. Whether measured by the absolute number of children they enrolled and renewed or relative to the targets they set, grantee progress varied in the first year. In general, strong progress toward meeting enrollment and renewal goals was associated with

- Participating in previous CKC grant cycles

- Being a health care provider

- Focusing outreach and enrollment activities on immigrant populations

Underperforming grantees were provided additional technical assistance to support improved performance during the second year of the grant period.

- In contrast, grantees focusing on rural populations enrolled or renewed fewer children and made less progress toward their targets than other grantees, largely due to challenges unique to this population. For example, transportation was a significant barrier in rural areas. Many rural areas lack affordable, convenient public transportation, making it difficult for families to attend outreach events or to visit a centralized enrollment center. Although grantees send outreach and enrollment workers to meet rural families where they live, their travel takes time and leaves fewer resources for other activities.

- A limitation of this evaluation is that it relies on grantees to self-report the number of children that apply, enroll, or renew coverage as a direct result of grantees' efforts. To promote accurate reporting, CMS requires grantees to verify that an application or renewal form resulted in an enrollment or renewal before reporting it. Verification by a state or county Medicaid or CHIP agency is best for data quality, but agencies are not required to respond to verification queries. Thus, grantees resort to alternative verification methods (such as following up with parents), which could result in underreporting. The actual number of enrollments and renewals is between 55,000 and 80,000, which are, respectively, the number of verified enrollments or renewals and the number of children for whom applications or renewal forms were submitted.

Activities

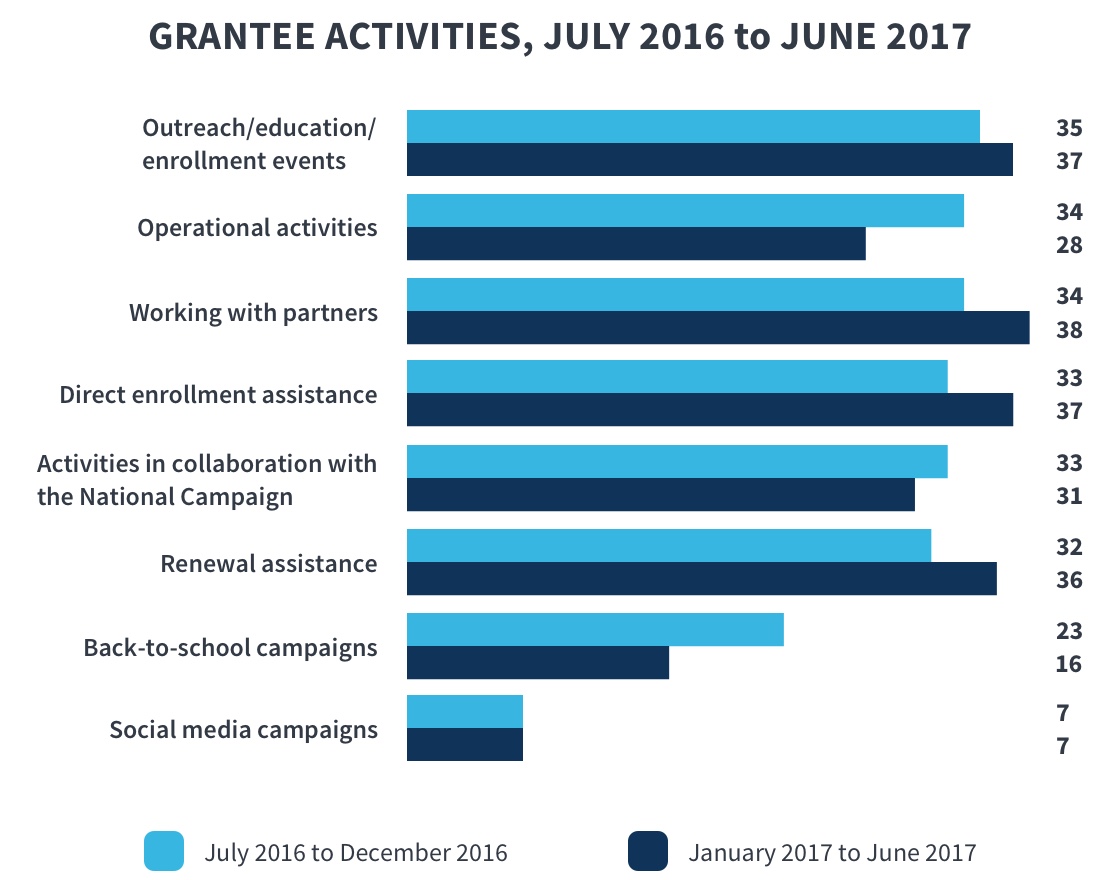

Grantees implemented a variety of outreach and enrollment strategies aimed at educating families about the availability of Medicaid and CHIP, identifying children likely to be eligible for these programs, and directly assisting families with the application and renewal process. With few exceptions, grantees expanded their activities from the first to the second six-month reporting period. For example:

- All grantees reported working closely with partner organizations by the second six months of the grant, often leveraging partners' service sites, community relationships, and other resources to reach more children and families.

- Grantees worked with the CKC National Campaign during Marketplace open enrollment and back-to-school periods, and most availed themselves of the Campaign's customizable outreach materials.

- More grantees provided direct enrollment and renewal assistance in the second six months of the grant, having used the first six months for start-up activities.

Challenges

Grantees faced a number of challenges:

- Sustaining operational capacity. Operational challenges were common. For example, all but one grantee struggled to build and maintain their staff. Some initially had trouble equipping remote staff with the technology needed to support online enrollment. First-time grantees reported more start-up challenges than those that had participated in prior grant cycles.

- Implementing partnerships and making them work. Although most grantees cited partnerships as vital to effective outreach and enrollment efforts, 20 grantees noted challenges with at least some partnerships. For example, some partner organizations performed poorly and some grantees underestimated how much time it would take to establish effective partnerships, which delayed or limited some planned activities. Nine grantees cited specific challenges related to school partnerships, such as having different priorities or having to deal with bureaucracies if they attempted to partner with schools.

- Verifying enrollment and renewals. During their first year of work, 32 grantees reported challenges with their processes for verifying and/ or tracking enrollments and renewals. Problems included negotiating memoranda of understanding or data-sharing agreements with Medicaid or CHIP agencies, and getting enrollment and renewal data in an unusable format or level of detail. For example, some grantees reported receiving aggregated rather than personally identified data, making it more difficult to track outcomes of individual applicants. Many grantees developed workarounds to verify enrollments and renewals. For example, some grantees followed up directly with families to verify enrollment and retention.

- Addressing long-standing barriers. A number of grantees noted perennial challenges of connecting eligible families to public coverage, such as low health and language literacy, providing required documents, and communication barriers. Some grantees said that the low-income families they serve tend to move frequently without always leaving a forwarding address, resulting in missed mailings about coverage or renewal opportunities.

- Dispelling public confusion. Grantees also said that confusion regarding availability of or eligibility for coverage was a great challenge to their work this year. For example, 19 grantees serving immigrant populations said they had to address fears about negative repercussions for accessing public benefits; another 9 grantees said that media coverage about efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act caused confusion about whether children's coverage was still available in their communities.

Lessons Learned

Grantees learned a number of important lessons to carry forward:

- Strong partnerships are worth the effort. More than three-quarters of grantees cited partner organizations' contributions as crucial to success. Partners can provide access to target populations; enhance grantees' credibility as trustworthy organizations; and expand grantees' capacity for outreach, enrollment, and renewal. Some partners can provide cultural competence and language skills that help grantees identify and enroll children in their target populations. Grantees reported partnering with many types of organizations, such as schools, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Head Start, and health systems. Grantees learned about the importance of communicating regularly with partners, developing trust, and identifying mutual interests to leverage partners' skills or goodwill.

- Rapport with families smooths enrollment and renewal processes. Quickly establishing rapport with families made it easier for grantees to follow up with those who expressed interest in application assistance but missed appointments, or needed reminding about documentation. Seeing how rapport facilitated grantees' progress toward their goals also helped grantees realize the importance of having staff and partners who were dependable, approachable, and linguistically and culturally competent.

- Monitoring and self-assessment leads to better outcomes. Perhaps the most valuable lesson, cited by a number of grantees, is that self-assessment resulted in improved performance during the first year of Cycle IV. Several grantees said that measuring their results led them to discontinue ineffective strategies and redirect efforts. Some grantees, especially first-time grantees, became more selective about outreach events and more geographically focused as a result of monitoring. By focusing their efforts they fostered better connections with their target populations.

Discussion

The first year of Cycle IV provides useful information for CMS about types of grantees that made the most progress enrolling and renewing children in Medicaid and CHIP, as well as those that faced the greatest challenges. Their experiences can help CMS set expectations and prioritize technical assistance activities for the second year of the performance period and for future grant cycles.

Factors related to stronger progress

As noted, grantees that participated in previous CKC grant cycles and grantees that are health care providers tended to enroll and renew more children than first-time grantees and non-providers, respectively. Experienced grantees had several advantages: they were more likely to have routinized outreach, enrollment, renewal, and verification procedures in place, and they had established partnerships from past efforts to support outreach and enrollment work.

Likewise, being a health care provider has several built-in advantages for connecting children to coverage. Providers have ready access to information about the insurance status of the children they see during office visits. When providers begin assisting a family with enrollment or renewal, they typically also have access to state databases that help them verify enrollments and renewals or identify problems to troubleshoot.

Grantees that focused on reaching immigrant communities enrolled and renewed more children, on average, than other grantees, as did grantees aiming to reach Hispanic/Latino children. The first-year evaluation data do not explain the relative progress of these grantees, however.

Health care provider organizations efficiently enrolled or renewed children already connected to the health care system. Other types of organizations focused on children who are harder to reach and may not have a usual source of health care.

Factors related to slower progress

In contrast to experienced grantees, first-time grantees were more likely to report early operational problems. Time spent finding and hiring qualified staff and developing mechanisms for tracking outcomes delayed some planned activities and likely contributed to slower progress toward achieving enrollment and renewal goals. In addition, establishing productive partnerships took more time and effort than expected for some new grantees, which delayed the start of outreach and enrollment efforts.

Grantees that geared their efforts toward children in rural areas were less successful than others, both in terms of the number of children enrolled or renewed and relative to the targets they set. Consistent with research on access to health care services in rural areas (Douthit et al. 2015), these grantees reported distinct challenges that might have contributed to lower-than-expected enrollments and renewals. For example, providing outreach and enrollment assistance in a rural area often entails considerable travel for project staff or the families they seek to help. Affordable and convenient public transportation is usually not available. In some cases lack of Internet access or electricity interfered with attempts to provide mobile application assistance. This meant grantees had to rely on paper rather than online applications, which take longer to complete and process. Moreover, grantees encountered reluctance to accept public health coverage on the part of rural families. They also found that building trusting relationships with rural families took more time and persistence than with other families.

Finally, more than two-thirds of rural grantees were also first-time grantees. Inexperience might have exacerbated the challenges that rural grantees faced, but it is also true that experienced grantees focusing on rural areas enrolled substantially fewer children than experienced grantees not targeting children in rural areas.

Implications for expectations and specialized technical assistance

Understanding the factors that helped or hindered enrollment and renewal progress during the first year of Cycle IV does not suggest that CMS should consider ruling out some types of grantees in future grant cycles. Rather, the mix of grantee organizations in a funding cycle should further the strategic objectives of the CKC program, and the expectations that CMS has about grantee targets and early progress should reflect an understanding of inherent challenges.

For example, although provider organizations can efficiently enroll and renew children who are already connected to the health care system, non-provider organizations are also needed to focus on harder-to-reach children without a usual source of health care. Thus, having a mix of provider and non-provider grantees (in addition to being statutorily required) is valuable to CMS's overall objectives. Likewise, if CMS aims to build outreach and enrollment capacity in a greater number of under-resourced communities, then investing in promising first-time grantees and in grantees that are committed to rural outreach and enrollment might be important ways to do that, despite challenges.

This evaluation suggests it would be useful to offer early and consistent technical assistance to grantees facing foreseeable challenges. CMS could help first-time grantees navigate start-up activities and accelerate enrollment by matching them to an experienced peer mentor and by providing start-up related technical assistance from the beginning of each grant cycle. Similarly, CMS could help grantees that work in rural areas by fostering a peer support network to promote problem solving.

Common technical assistance needs

Similar to previous grant cycles, some grantees experienced problems or delays when they tried to verify enrollments and renewals with their states. Most grantees eventually switched to an alternative method, if needed, but some might have been able to verify more enrollments and renewals had they switched sooner.

Nearly all Cycle IV grantees emphasized the importance of partnerships to their first-year progress, but not every partnership was beneficial. The general topic of forming and maintaining effective partnerships for outreach and enrollment has not been a technical assistance emphasis for Cycle IV grantees, but it should be considered for the Year 2 performance period and future grant cycles. Presentations by outside speakers, peer support from grantees with partnering experience, and a toolkit to support effective partnering could all support this crucial component of connecting children to coverage.

Continued learning opportunities. The first-year evidence helps explain some of the variation in grantee progress, but there are likely other factors at work. These include specific aspects of partnering, factors that affect ease of access to target populations, the particular combination of activities a grantee deploys, and more intangible factors such as the intensity of services provided or the qualities of individual staff. Two sets of site visits are planned for the second year of the Cycle IV. Visits to five high-performing grantees should help inform CMS's understanding of the qualities and practices that have helped some grantees flourish this year, and whether others can replicate these practices. Visits to another five grantees that are underperforming will focus on identifying challenges and providing technical assistance to help boost enrollments and renewals for the rest of Cycle IV.

References

Current Population Survey. "Children by Type of Health Insurance and Coverage Status: 1997." Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, March 1998. Accessed July 5, 2018.

Douthit, N., S. Kiv, T. Dwolatzky, and S. Biwas. "Exposing Some Important Barriers to Health Care Access in the Rural USA." Public Health, June 2015, vol. 229, Issue 6, pp. 611-620. Accessed February 27, 2018.

Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. "Health Coverage for Parents and Caregivers Helps Children." Washington, DC: Georgetown University Health Policy Institute, Center for Children and Families, March 2017. Accessed June 20, 2018.

InsureKidsNow.gov. "Connecting Kids to Coverage National Campaign." Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, not dated. Accessed June 21, 2018.

InsureKidsNow.gov. "Outreach and Enrollment Grants." Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2017a. Accessed September 28, 2017.

InsureKidsNow.gov. "2017 American Indian Alaska Native Cooperative Agreements." Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2017b. Accessed June 21, 2018.

Kenney, Genevieve M., Jennifer Haley, Claire Pan, Victoria Lynch, and Matthew Buettgens. "Children's Coverage Climb Continues: Uninsurance and Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility and Participation Under the ACA." Washington, DC: Urban Institute, May 2016.

Kenney, Genevieve M., Jennifer Haley, Clare Pan, Victoria Lynch, and Matthew Buettgens. "Medicaid/CHIP Participation Rates Rose among Children and Parents in 2015." Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, May 17, 2017.

The source for all figures in this report is Mathematica’s analysis of grantees’ semiannual reports for the period July 1, 2016, to June 30, 2017.